The previously untold story of the brilliant Russian concert pianist Gregory Haimovsky is revealed in Marissa Silverman’s new book for University of Rochester Press. Exiled by the Soviet regime, Haimovsky found a way to perform the “banned” Western music of Olivier Messiaen and fight the USSR’s cultural prohibitions. Gregory Haimovsky, Gorky Conservatory of Music, 1960, …

Category: Uncategorized

#iamFOR

According to artist Paula Crown, the #iamFOR exhibition on display at the For Freedoms headquarters incorporates, examines, and explores themes of environmentalism, racial awareness, and identity politics.

Located in the heart of the Meatpacking District in NYC, onlookers are provocatively greeted by and confronted with Crown’s environmentally probing piece, Humble Hubris: Don’t know what you got (till its gone) bench (2018), outside Fort Gansevoort, at 51 Gansevoort Street, NYC: “If you think you’re hot now, just wait.”

This statement, especially given its location—which is surrounded by all kinds of NYC construction—makes obvious the tangled mess of urbanization, commercialization, and industrialization. Notice, too, how Crown’s piece is juxtaposed with the seemingly dead vines clinging to the lattice work outside the edifice and the winding coils of cables adjoined to the outlet in back of the artwork. What does all this mean?

Additionally, situated in the window just around the corner from Humble Hurbis are Not banners (2018). As stated by the exhibit:

In the 18thcentury, anthropologists and cartographers created hierarchies and vocabularies that continue to haunt us, labeling the world with colonial perceptions of human difference. Classification of human beings by color is a social construct dismantled by scientific truth. Artist Paula Crown’s NOT paintings prompt viewers to compare themselves with the subjective taxonomies of the past, to invalidate prior modes of categorization and to demand nuance and agency.

Moreover, it is worth noting that one of the construction signs posted next to Fort Gansevoort, and catty-corner to the Not banners, is a call for vehicles to “use alternate” means of maneuvering through the area. Of course, neither the For Freedoms group, nor Crown, would have expected this kind of coincidence. That is, it is provocative that NYC is asking motorists for “caution” and to take alternative traffic routes when Crown invites her artwork visitors to reconsider the routes they use to move through the world!

There’s much more to the #iamFOR exhibition. If you happen to be in NYC, be sure to experience it for yourself.

London’s Fourth Plinth

For those who may not know, London’s Fourth Plinth is located in Trafalgar Square. The other three plinths, or platforms, contain sculptures of military officers: Henry Havelock, Charles James Napier, and King George IV. However, the fourth remained empty due to a lack of funding, unused for 150 years. That is until London’s Royal Society of the Arts developed the Fourth Plinth Project. The project maintains a revolving public art exhibit in order to celebrate, question, and engage with the world today through art-making. In fact, the Fourth Plinth hosts a series of commissioned artworks by world class artists and is the most talked about contemporary art prize in the UK.

So, what is on exhibit now?

On March 28th, Michael Rakowitz’s “The Enemy Should Not Exist,” was unveiled. The work “depicts a re-creation of Lamassu, an Assyrian statue that stood in Iraq in the ancient city of Nineveh, on the outskirts of modern-day Mosul, until 2015 when the militant group destroyed it along with other irreplaceable works of ancient art.” The work is made of 10,500 recycled cans of syrup made from dates (dates being an important export of Iraq).

Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, stated: “One of the reasons we should be so proud is this piece of art is from an Iraqi American of Jewish faith to be displayed in the greatest city in the world … And the creation and installation of this piece of art is an act of resistance against the tyranny of religious fanaticism. It is an act of resistance against the acts of philistinism. But it is also a celebration of who we are as a city: confident in who we are, pluralistic, welcoming and diverse.”

From London: Artists as Citizens

Just returned from the “Reflective Conservatoire Conference: Artists as Citizens.” This inspiring, 4-day conference showcased, among other things, a variety of arts projects that illustrate how the arts do their good work.

In doing so, the conference asked the essential and age-old question: What do artists do? Undoubtedly, artists view the world in unique ways. And, through their artwork, help us confront our realities—the good, the bad, and the ugly. Thus, at the heart of this kind of work is the concept of “artistic citizenship” and being an “artist-as-citizen.”

Meet one artistic citizen: Helen Marriage. Director of “Artichoke,” Marriage stays clear of traditional “artistic spaces”— the gallery, concert hall, theater or dance studio—and instead transforms the streets, squares, gardens and coastlines of the public spaces around the UK.

In her talk, “Beyond the institution: Working the streets,” Marriage spoke about disrupting public spaces “with an objective to work with artists to create extraordinary, large-scale events that appeal to the widest possible audience.”

At the heart of Marriage’s projects is accessibility and equity, and the notion that all people have the right to experience artwork for free.

One such project was Great Fire 350, dedicated to commemorate the 350th anniversary of the London fire of 1666.

While this project, one among many, speaks for itself, a few aspects deserve special mentioning. Throughout 2016, London marked a season of exhibitions, concerts, lectures, and tours. A festival, really, of the power of the arts to provoke the imagination, Great Fire 350 included an underwater performance art-work, a domino-esque sculpture that snaked throughout London’s streets, which outlined the various roadways of the 1666 fire, and ended with a live re-burning of a model of 1666 London on the Thames River. This grandiose festival implied numerous aspects about social life. Primarily, though, Great Fire 350 highlighted a beautiful and powerful resilience of a city and its peoples to be re-born.

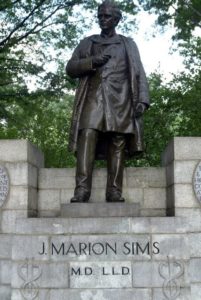

When Statues Hurt

In an open letter, academics and artists have urged NYC Mayor de Blasio to remove five public monuments and statues they say exhibit and promote racism.

Importantly, we must ask: Do these statues qualify, though, as art? If so, why so? If not, why not? And why should we ask such questions in the first place? Do these questions matter against the larger issues of racism and prejudice?

Questions worthy of our consideration…

New Series Announcement

From Plato to Public Enemy, people have debated the relationship between music and justice—rarely arriving at much consensus over the art form’s ethics and aesthetics, uses and abuses, virtues and vices. So what roles can music and musicians play in agendas of justice? And what should musicians and music scholars do if—during moments of upheaval, complacency, ennui—music ends up seemingly drained of its beauty, power, and relevance?

University of Michigan Press is proud to announce a new series, Music and Social Justice. This endeavor welcomes projects that shine new light on familiar subjects such as protest songs, humanitarian artists, war and peace, community formation, cultural diplomacy, globalization, and political resistance. Simultaneously, the series invites authors to critique and expand on what qualifies as justice—or, for that matter, music—in the first place. Music and Social Justice lends a platform for writers who wish to submit traditional scholarly monographs. The editors are equally enthusiastic to work with authors and artists who wish to unsettle the discursive norms of conventional academic prose in the name of rhetorical experimentalism, anti-capitalism, neurodiversity, and radical collaboration.

Music and Social Justice has assembled an Advisory Board who are active and activist leaders in their fields: Naomi André, Suzanne G. Cusick, Ellie M. Hisama, Mark Katz, Alejandro L. Madrid, Darryl “D.M.C.” McDaniels, Carol J. Oja, and Shana L. Redmond. The Advisory Board will work closely with the editors to seek out prospective authors, open lines of communication, and review submissions.

For more details on the impetus behind the series, including short interviews with the Advisory Board, please see http://musicologynow.ams-net.o

Please direct queries and proposals to series editors William Cheng (william.cheng -at- dartmouth.edu) and Andrew Dell’Antonio (dellantonio -at- austin.utexas.edu), or University of Michigan Press Editorial Director Mary Francis (mfranci -at- umich.edu).

Music and Social Justice Resources Project

The Society for Ethnomusicology is currently collecting news items to include in its online repository: applied project news, educational outreach program news, organizational endeavors, and research projects. We are grateful to and inspired by the Society for Ethnomusicology and their thoughtful attention to connections between music and social justice.

The Society states:

The Society for Ethnomusicology’s Music and Social Justice Resources Project is a repository of material on how people worldwide are currently using music to address issues of social conflict, exclusion/inclusion, and justice. We welcome notices on public events (e.g., rallies, performances, conferences) and other general news; proposals/reports on projects involving community engagement, activism, or advocacy; syllabi, lesson plans, and other educational material; information on activist organizations; and research articles.

To submit initiatives related to music and social justice for inclusion in the online repository, go here and follow the online instructions.

By way of example, meet Musicians Without Borders. Founded officially in 2000, this world-wide organization has been working with local musicians and community organizations to build sustainable community music programs. Why music? The organization states:

Where war has raged, people need everything to return to life: food, water, shelter, clothing, medicine. But more than anything, people need hope. To reconcile, people need empathy. To heal, people need connection and community.

Music creates empathy, builds connection and gives hope.

Rwanda Youth Music is one of many of Musicians Without Borders’ projects.

The Very Decency of Paula Vogel’s “Indecent”

Paula Vogel’s Indecent is a play about our past, present, and future; it is a play about the many ways society judges its people; it is a play about GLBT rights; it is a play about the good and bad of humanity; but it is also a love story—a love for theater and the transformative powers the theater holds for audiences and players alike.

Structured as a play within a play, Indecent retells the history of Sholem Asch’s 1907 Yiddish drama, God of Vengeance. After touring the world to critical acclaim, and at its Broadway debut at the Apollo Theater on 42nd Street, Asch’s work was shut down in 1923 for obscenity; all the actors were arrested given the drama’s exploration of same-sex love. Asch’s work is pinned against the backdrop of anti-Semitism—additionally, general anti-immigration sentiments—in the United States. So largely, Vogel’s Indecent illustrates the ways in which the oppressed maintain their identities and dignity when pushed to the margins.

Interestingly, Asch’s play is as relevant today as it was, then, when it toured the world. And so Vogel’s prism-view of God of Vengeance refracts the very essence of today with incredible clarity and precision. Vogel states:

I didn’t anticipate that Indecent would be as relevant today as it is; we are witnessing an upheaval of fear, xenophobia, homophobia, and, yes, anti-Semitism. We are in the midst of the strongest white nationalism since the 1920s when American borders were closed to immigrants. In this moment of time we must say that we are all Muslim. We must reclaim the importance of our arts and culture. We must remember where the closing of borders in the 20th century led nations around the globe.

Crossing Point Arts

Can the arts make crucial differences for those in need? Meet Crossing Point Arts. This non-profit organization harnesses the social, cultural, emotional, and political power of the arts and helps survivors of human trafficking reclaim their sense of selves through art-making. From their website:

Crossing Point Arts was founded by a small group of New York City activist artists. This group came together to offer their hearts – and their art forms – to survivors as a step towards managing Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). In workshop format, participants have the opportunity to be guided by Teaching Artists and Expressive Arts Therapists in singing, song-creation, dance, visual arts, poetry and theater.

The mission of the organization: “to bring the healing and restorative power of the arts to survivors of human trafficking through expressive arts workshops, helping them to release trauma, reclaim their once-silenced voices and learn long-term coping strategies.”

See their newsletter here: Crossing Point Arts – Spring Newsletter No. 5

Concert for Peace

Thank you, Michael Bussewitz-Quarm, for your support of our book. Yes, collective singing — all collective music making — is a powerful and potent source of good depending on the contexts and circumstances of the musicing.

Because of this, thank you in advance for your “Concert for Peace”!

For those interested in the Thomas Turino quote from Artistic Citizenship that speaks to the above:

“The topic of music and social change conjures up images of dramatic political moments such as the freedom songs of the Civil Rights Movement. In that movement, it was the very act of collective singing as much as the content of the lyrics—“We Shall Overcome”—and associations of the tunes with the Black Church and previous labor movements that galvanized protesters. Collective singing illogically steeled regular people to put themselves in harms way, to lovingly turn the other cheek, to peacefully face rocks, sticks, bricks, fire hoses and police dogs. Similarly, in Germany during the 1930s and early 1940s, collective singing of Nazi songs was common among people at the end of work days, among youth at summer camps, and among average citizens at many social gatherings. Again, it was the repeated act of massive collective singing as much as the content of the lyrics—“Work, Bread, and Death to the Jew”— that helped prepare normal citizens, again illogically, to acquiesce to, and even participate in mass murder. In both cases music functioned in very much the same ways to alter peoples’ consciousnesses, to prepare them for heroism or villainy—to be the very best or the very worst humans can be.” (“Music, Social Change, and Alternative Forms of Citizenship,” p. 297)